Political party leaders often claim their plans and policies represent what “the people” want, or at least reflect the opinion of the majority of their voters. Yet our colleagues professor Goda Perlaviciute, associate professor Thijs Bouman, and post doc Žan Mlakar say there is one topic that most voters support that politicians rarely campaign on: stronger climate policy.

In a recent column by Pieter Derks on Radio 1, the cabaretier cleverly identified who exactly most political parties in the Netherlands see themselves as representing: “the people at home” (the average voter). He went on to quote all the times that leaders of political parties – both left-wing and right-wing – referred to “the people at home” and what they want from their elected officials.

“It’s a very clever way to position yourself as a politician outside or above The Hague politics. All the others are preoccupied with each other, but I am preoccupied with the people at home. As if all those people at home think the same way,” said Derks.

Campaigning for policy in the name of the average Dutch citizen suggests a mandate informed by the values and priorities of the majority of the Dutch electorate, yet research suggests that political campaigns might not accurately represent what people want with regard to climate policies.

People are concerned about climate change and want more action

Despite their many assertions that they represent the majority, political party leaders talk relatively little about one of the rare issues where there is genuine consensus, namely support across the political spectrum for stronger climate policy.

While climate action is rarely at the center of political campaigns, research from the Environmental Psychology department at the University of Groningen, other social scientists, and a growing number of Dutch, European and international surveys suggests mass support for stronger climate policy: a vast majority of the population (80-90%) wants intensified governmental climate action.

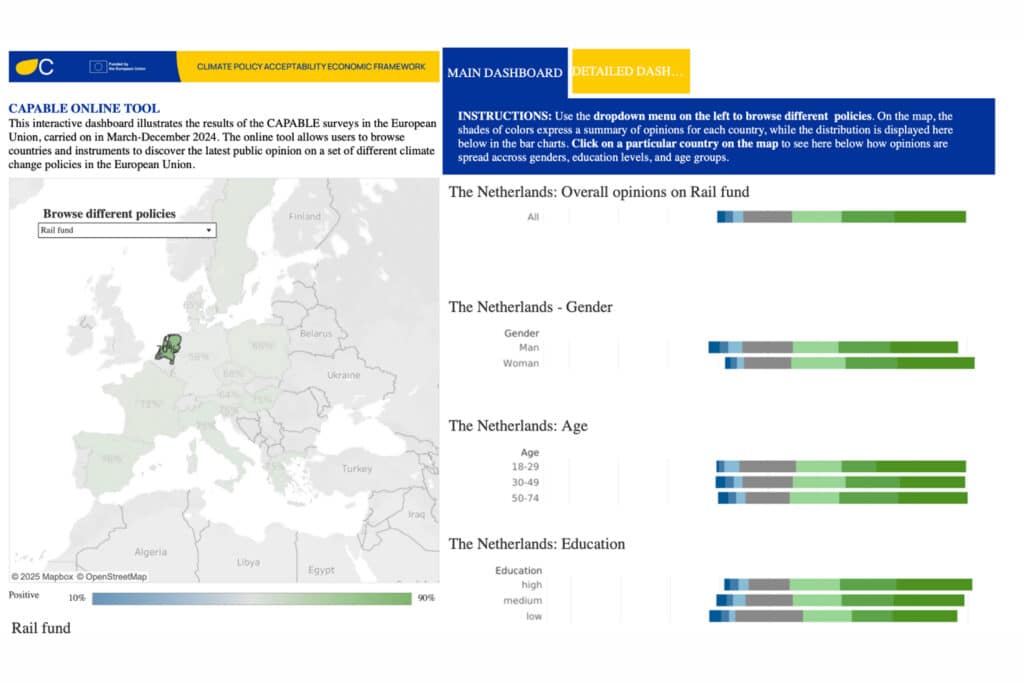

A 2023 survey by the European Commission found that 87% of respondents think it is important that their national government take action to increase the share of renewables in the energy mix. A recent study Perlaviciute, Bouman and Mlakar were involved with through the CAPABLE EU Horizon Europe project found that many EU citizens are willing to support various forms of climate policy, with subsidies for train travel and home insulation scoring particularly high, and taxes on behaviors like driving or eating meat proving less popular.

This also holds true in The Netherlands: a study by Ipsos I&O on behalf of the Dutch climate advocacy group Milieudefensie found that eight out of ten people in the Netherlands believe that companies should comply with the Paris Agreement. Similarly, the Dutch Scientific Climate Council reports that 75% of Dutch adults are concerned about climate change and protecting nature and the environment.

Not opposed to climate policy

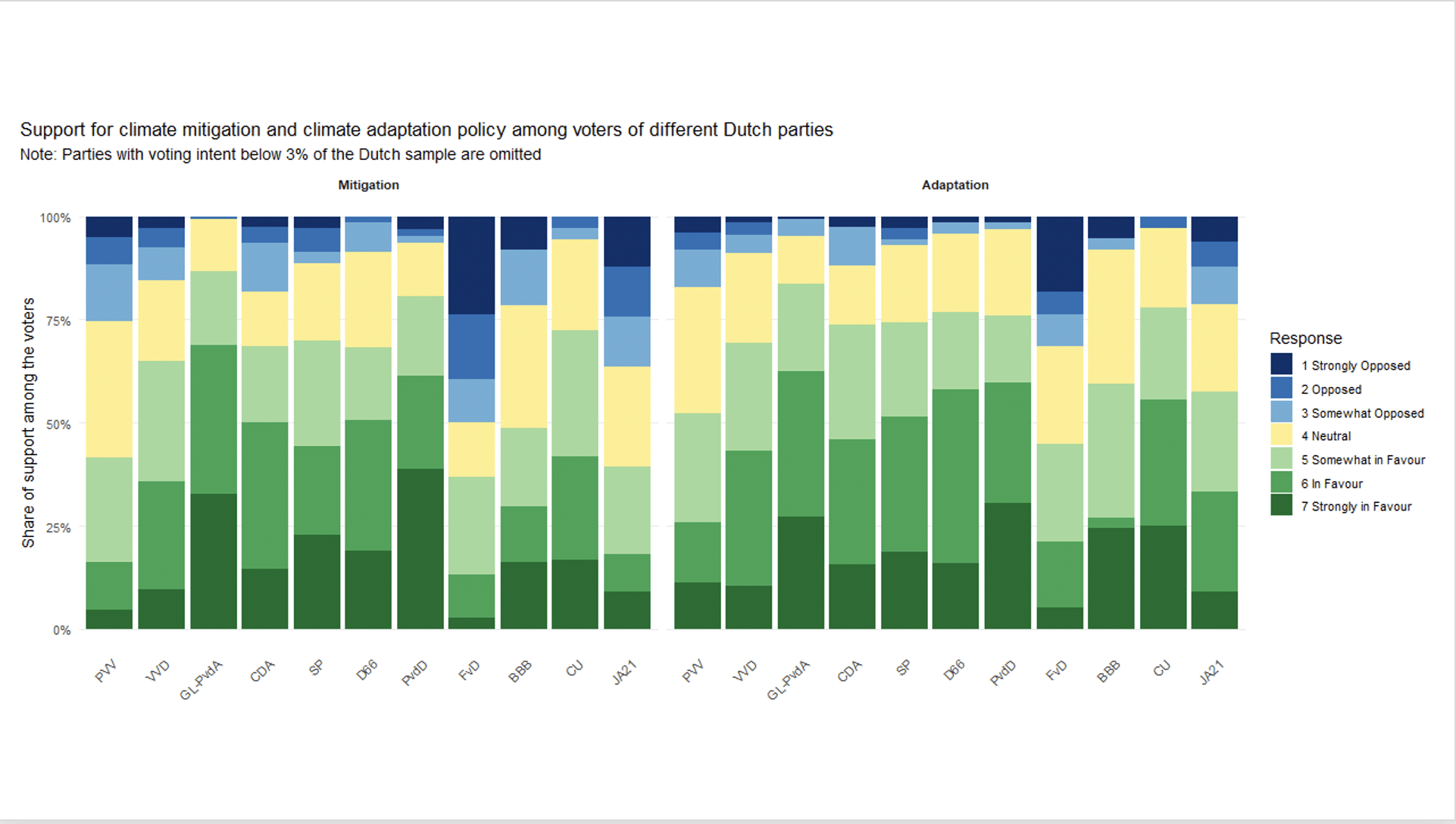

Also through CAPABLE, the EP Groningen researchers conducted a survey* in the Netherlands which revealed that the entire spectrum of voters, spanning different political parties, are supportive of climate policies.

In June of 2025, they asked 1,200 people who were representative of the Dutch population if they would vote, which party they would vote for, and to what extent they wanted two types of climate policy:

climate mitigation: slowing down climate change by increasing renewable energy sources and reducing greenhouse gas emissions from transportation and agriculture

climate adaptation: adjusting to and preparing for climate change, i.e. making homes and infrastructure more durable and resistant to damage, and preparing for extreme weather events that are more likely and more severe due to climate change

Here is what they found:

For most voters, support for (or lack of opposition to) climate policy was the majority view. As of 25 October, the four parties performing best in polling by Ipsos were PVV, CDA, GL-PvdA and D66. In the CAPABLE survey, this is how much the voters for those parties said they were either in favor of or neutral about mitigation and adaption:

PVV: 73% for mitigation, 82% for adaptation

CDA: 82% for mitigation, 88% for adaptation

PvdA-GL: 98% for mitigation, 96% for adaptation

D66: 91% for mitigation, 96% for adaptation

A right wing vote is not an anti-climate vote

A 2024 paper by Bouman (et. al.) found that the majority of voters worldwide favor their governments taking stronger climate action. Be that as it may, people could still oppose specific climate policies that they perceive as unfair, or plans that they worry could negatively impact their quality of life.

If most people are supportive of intensified climate action, then why do they vote for parties that do not seek to accelerate climate policy? To put it simply, a person who votes for a party that doesn’t prioritize combating climate change is not automatically someone who doesn’t care about, or denies, climate change. It is likelier to mean that those voters see other issues as being more important, and that they deserve not to be neglected: right wing voters “share concerns about job security, immigration, bureaucracy, and costs of living, issues they and these parties prioritise”, the researchers write.

Inaccurate impression

Bouman and his co-authors identified three reasons that politicians may be under the inaccurate impression that voters do not support strong climate policy:

- High carbon emissions behavior (like flying and eating meat) attracts and receives more media attention, whereas sustainable progress and willingness to change get less attention

- Unsustainable behaviours are frequently seen as intentional, even though in reality they are more often a result of convention or ease, like driving a car instead of cycling because infrastructure favours vehicles. Such behaviors occur because of the contexts that existed before their sustainability impacts were well understood.

- The voices of economically powerful and influential actors with vested interests in weak climate policy are often louder than the voice of the general public

Other research from Environmental Psychology Groningen reaffirms that public opposition is more likely to arise from concerns about the fairness, feasibility, and impacts of environmental action, rather than inherently disliking climate policy.

Effective, feasible and affordable climate policy

That means that any politicians who want to tap into that widespread support should create climate policies that are effective, feasible and affordable, because those are most likely to appeal to voters from different political affiliations. Legislation that distributes the costs and benefits of climate policy more fairly across society and is based on transparent decision-making will also probably enjoy broader public support.

Climate policies like insulation subsidies, promoting slow travel, and making plant-based diets more affordable and accessible have the added benefit of avoiding or alleviating negative impacts on other things that people value, like health and finances, which in turn means that they will stand the best chance of being embraced by the general public.

Another recent paper from the EP Groningen group reaffirms that all levels of Dutch society believe there is an important role for everyone to play in limiting climate change, and that governments and businesses in particular can lead by example. PhD Xinran Wang and professor Linda Steg found that all societal actors (government, financial sector, businesses, NGOs, media and Dutch citizens) saw governments and businesses as the group most responsible for limiting climate change, most capable of taking climate action, and as the actors whose actions will be the most effective in helping to limit climate change.

What the people at home really want

Climate change is one of the biggest challenges we face, and urgent action is needed on all levels of society, from the people at home to businesses and politicians, to ensure that the risks from climate change do not get any worse.

An important message to politicians who seek to represent “the people at home” is that most people support climate policies, and that policies that make climate actions feasible, affordable and appealing are more likely to generate wide-spread support and adoption.

*The data was collected by professor Goda Perlaviciute, associate professor Thijs Bouman and post doc Žan Mlakar, who are all part of the Environmental Psychology research group within the Faculty of Behavioural and Social Sciences at the University of Groningen, on behalf of the Horizon EU CAPABLE project. The following researchers and academic institutions also contributed to the data collection:

ETH Zurich: E. Keith Smith, Lea Stapper, Alessio Levis, Thomas Bernauer

CMCC: Mary Sanford, Silvia Pianta, Johannes Emmerling, Massimo Tavoni

IESEG/CNRS: Loïc Berger, Thomas Epper, Uyanga Turmunkh, Maria J. Montoya-Villalobos

UAB: Jeroen van den Bergh, Ivan Savin

CUNI: Milan Ščasný, Iva Zvěřinová

The views expressed in this blog are those of the blog author only, and do not represent the views of other people in the consortium nor of the European Union.